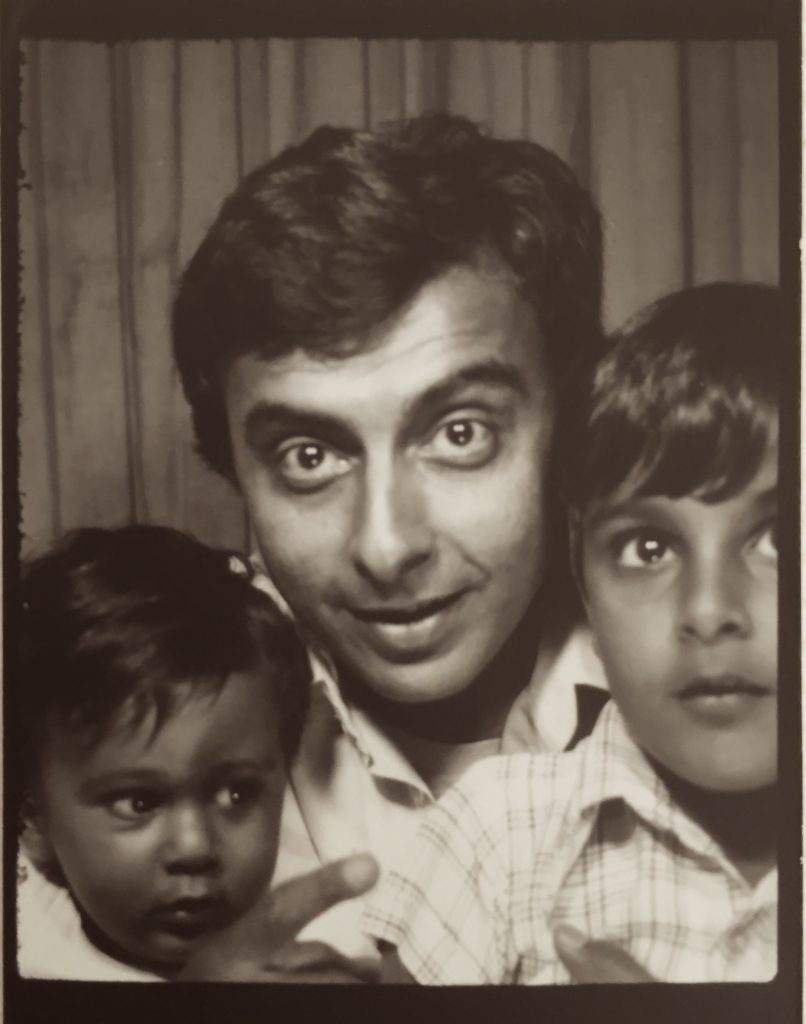

My father never wanted me to be a psychologist. In fact, I remember when I lived at home as an undergraduate student, I would hide my “Department of Psychology” mug in the back of the cupboard, to avoid him looking disgruntled whenever he saw it. Although I knew the separate reasons he articulated to me for this frustration, I don’t think I pieced them together as a full concept until after I moved into the area of consulting psychology.

I knew, we were a family of immigrants. I knew, my parents moved so my brothers and I would have an opportunity for education and upward mobility that we would not have had in Tanzania. I knew, they faced unrelenting discrimination as a price for these opportunities, especially in the workplace. What I had not realized (despite having heard the stories) was that their experiences were common to immigrants, people of colour, women of colour, and other marginalized groups. Though I knew the stories, I don’t think I realized the full extent and cost of these experiences (overt or covert) until I studied psychology. But also as I experienced discrimination in the professional and academic world myself, then, I finally understood that look on my father’s face and all the realizations and fears that came with it, when on those mornings, my mug was at the front of the cabinet.

Initially, the stories my father and mother would bring home from work were comical. They were the “can you believe this happened today?!” type of stories. The most common thing said to both of them was that they “speak amazing English.” What most people did not realize is that they spoke English (among several other languages) all of their lives. Tolerant and explanatory at first, the weight of these comments changed my parents’ response from eye rolls to a burdensome weight that continuously left them feeling like outsiders.

My father was mischievous. Once when a customer told him how good his English was, he told him that he had learnt English a week after his arrival to Canada, by watching Sesame Street. The customer then turned to his son who was with him, and started shouting, “these immigrants learn English from a kid’s show in a week, and you don’t even know math after you’re taught it for a whole year!” “Poor kid,” my father thought. “My poor father,” I think now.

These small but sharp cuts were manageable at first but eventually bore a weight on my parents and their opportunities for success. My father was exceptionally great at sales. Visit his food store now, and you’ll leave with a basketful of goods as a testament to this. But prior to his own business, he moved up quickly into management positions. But as he did, he hired other people of colour, and his success continued. But the “face” of the store was not what upper management desired, and he was told, explicitly, to stop hiring people of colour and immigrants. When he refused, stating he just hired the best people for the job, he was terminated.

When he moved to a management position of another major retail firm (still thriving today – still presenting a relatively White image), and still hiring people of colour and immigrants, he was told the same thing about hiring practices, and again terminated after continuing to hire people of colour and Canadian newcomers. His lesson to me, many times over; a person of colour or immigrant leading their stores to success was acceptable, as long as people of colour remained the minority.

The stories are countless. Being invited back for interviews, but not given a job because management wanted to train how to interview “people like you” (he was told). My mother being told she would only be hired if she removed her hijab, or that her hijab made “customers feel uncomfortable”, or that it did not reflect the company brand. Not being offered jobs commensurate with experience, but hiring less qualified White men into those roles. Not being allowed to sell items in commission-based jobs until the toilet was cleaned several times a shift – even though this was not a part of the job description. Being fired or demoted if these concerns were brought to the attention of management. And often, being the victim of openly racist and sexist remarks.

Frustrated with these experiences, my parents opened their own business, which they still run today. A small specialty food shop in central Winnipeg. By then, my father was under the belief that people of colour would rarely be allowed into leadership roles in a North American (predominantly White) workforce. And that the only way his children could avoid what he went through was to become a professional relied upon heavily by society.

My father would say to us, “get a job where you are needed, so no one can fire you because you’re not White. If they need you, it doesn’t matter what colour you are.” For many other immigrant families, it’s a common joke that their children are forced into one of three professions; to be a lawyer, an engineer, or a doctor. The rationale for many might be the very same. But for my father, the only option was a doctor – and not the PhD kind.

Having not known the prospects of success associated with being a psychologist, my father worried immensely that I would face the difficulties he did as a young man. Though he is incredibly proud of me now (much to my embarrassment, telling most shoppers in his store about the times I was on TV or the radio for interviews), he had previously worried his sacrifice would be for naught. That disgruntled look on his face whenever he saw my Department of Psychology mug was not of anger, but of fear.

Though this article may be read as a reflection of problems that existed in the 80’s and 90’s, organizations still face a great deal of difficulty when it comes to issues of diversity and inclusion. In 25 years, discrimination against Black people has not declined. Discrimination based on gender, age, and ethnicity in the workplace still remains a viable problem. And research confirmswe still tend to have a bias that promotes White people into leadership roles. And this, White standard in leadership is so clearly visible to this very day, be it CEO’s, Prime Ministers, Presidents, or heads of departments. Though it’s hard for any child to admit their parents were right, it appears my father worries were founded. And issues of inclusion still remain a problem today, 35 years later.

The hope now is that the discomfort of discussing my parents’ stories (andthose of today’s generations) help us create an ease in not just identifying but also improving inclusion in today’s modern workplace. Without these discussions, without an understanding of the psychology of these experiences, we will remain largely complacent and perpetuate a problem that is too costly. Even as a person of colour, even with the lived experience of having been an immigrant, and witnessed my parents and my own struggles, it was not until I reflected up on them and studied them, that I was able to obtain my own insight need to grow and then help others understand as well. It makes sense then, that we also make efforts to understand the lived experiences of those different from us, if we are truly going to work toward this goal of inclusion.

What strikes me most though is the irony that I have come full circle. I am engaged in a job my father was reticent about, now attempting to improve inclusion in the workplace – the very thing he wanted.